The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is disrupting many dimensions of our daily lives and raising questions about how public health and socio-economic shocks are affecting people, particularly children, experiencing disadvantage. At the Paul Ramsay Foundation, we are supporting action both to address the acute needs arising from these disruptive events and to anticipate the opportunities that might emerge more slowly, concerned that the pandemic may exacerbate inequalities already entrenched in Australia.

Before the pandemic, education outcomes for Australian students were already related to the socio-economic status (SES) of a child’s family. Analysis from the Mitchell Institute in the Educational Opportunity 2020 report paints a sobering picture.

- 67.7% of low-SES children start school developmentally on track compared to 85.3% of high-SES children.

- 50.6% of low-SES children achieve the national minimum standard for literacy and numeracy in the middle years of school compared to 91.3% of high-SES children.

- 66.8% of low-SES children attain a Year 12 certificate or its equivalent compared to 91.8% of high-SES children.

Against that long-term background, at the height of the pandemic, Australian schools accomplished an unprecedented feat by shifting to online and remote delivery of education in a matter of days. The rapid transition in school delivery resulted in a disruption for all school children. However, there are few comparative or historic experiences at this scale and speed of disruption to inform educators or parents about how to tailor support for children already at risk. Many scholars and policy-makers anticipated that pre-existing disadvantage could create disproportionate challenges to learning during COVID-19 lockdowns. Given their need to focus on the immediate challenge of delivering remote learning, governments had little capacity to consider these specific needs or the medium-term effects of the disruption on students, especially those at risk of compounded disadvantage.

As the pandemic disruptions began, think tanks and researchers immediately identified the concern that the pandemic might make existing disadvantage worse and turned to the existing evidence base to draw useful lessons. The Grattan Institute and the Centre for Independent Studies produced reports that predicted the impact learning from home would have on students’ learning outcomes and offered immediate policy recommendations. The Commonwealth Department of Education, Skills and Employment (DESE) commissioned six eminent Australian researchers to report on the likely impacts of remote learning. All this work, generated early in the pandemic, had the virtue of being timely and based on evidence. But it had the necessary vice of being based on past evidence and estimates that could be derived from that evidence. The challenges of this kind of approach became manifest as others internationally turned their minds to the same challenge, and eminent researchers cast doubt on some of the assumptions underpinning the estimates in Australia.

To address these gaps, we partnered with the Institute for Social Science Research at the University of Queensland to support the Learning through COVID-19 project, an intensive study designed to understand what happened during the pandemic for students already at risk of educational disadvantage, to identify the needs that have arisen for them, and to propose evidence-based solutions for the consideration of governments, funders, non-profits and schools.

The study focuses on the experiences of three cohorts of school students, all of whom entered the pandemic at greater risk of educational disadvantage:

- Students in the early years of primary school who started school developmentally vulnerable

- Students in the last three years of secondary school who were at risk of disengaging from formal schooling

- Students who have had contact with the child protection system.

This month our partners at ISSR released the last of three reports from the study. Taken together, the reports describe what we knew about the three cohorts prior to the pandemic, provide an empirical snapshot of their educational experience through the pandemic’s disruptions in mid-2020, give an overview of how the pandemic’s disruptions may have affected students’ educational outcomes, and synthesise rigorous evidence to provide guidance about programs and approaches that can work to address educational disadvantage in the wake of the pandemic.

These insights are important because they give an objective and more granular picture of whose education was most affected by the pandemic, the risk factors that were most amplified, the needs that policy and service responses need to address, and courses of action that the existing evidence suggests may be effective in addressing those needs.

The sections below highlight key findings from each report.

Pillar 1 Report – Key Findings

The first report from the study (1) describes what we knew about the three cohorts prior to the pandemic and (2) reviews the international literature and public documents released from state and territory governments to describe early educational responses to the pandemic disruptions. The study recognises that learning outcomes are influenced by many factors across a young person’s life, including themselves, their family, their school, their community and the wider social environment. Drawing on that understanding, the study has several important findings:

Pillar 2 Report – Key Findings

The second report examines large education data sets in New South Wales and Tasmania to identify aspects of educational disadvantage that were exacerbated because of the pandemic. It also analyses interviews with young people experiencing disadvantage and their families, academic experts, and leading service providers to shed light on students’ experience of education through lockdown that were not apparent in the larger data sets. This part of the study began before it became apparent that Victoria would have a longer lockdown than other states, and it does not include statewide data from Victoria.

The report has several important findings.

- Gaps in student engagement in learning did not widen during the lockdown period between two cohorts and their more advantaged peers.

- Attendance gaps grew for two cohorts of students – those starting school developmentally vulnerable and senior students at risk of disengaging from education – and the increased gap for the senior students was potentially caused by the pandemic.

- Available data on students who had contact with the child protection system did not allow the researchers to draw conclusions about the impact of the pandemic on their learning.

- Students reported negative impacts on their wellbeing because they felt ‘stuck’ in one location, they had fewer opportunities than normal for family, social and peer connections, and they were not able to mark important milestones or events, such as family trips and graduations.

- There were positive aspects of remote learning for some cohorts of students, and students exhibited strength and resilience despite the stress of the pandemic.

- Despite increased feelings of anxiety and stress during the lockdown, all students interviewed still planned to finish school and move on to work or further study.

- Students with sensory needs or mental health issues reported that remote learning was less stressful.

- Some students with social anxiety reported benefitting from learning at home.

- Students who attended flexi-schools said that their schools were very supportive prior to lockdown, and that level of support continued throughout the lockdown. Students at flexi-schools were the most likely among those interviewed to say that they could ask for support from their school and have it offered to them.

Pillar 3 Report – Key Findings

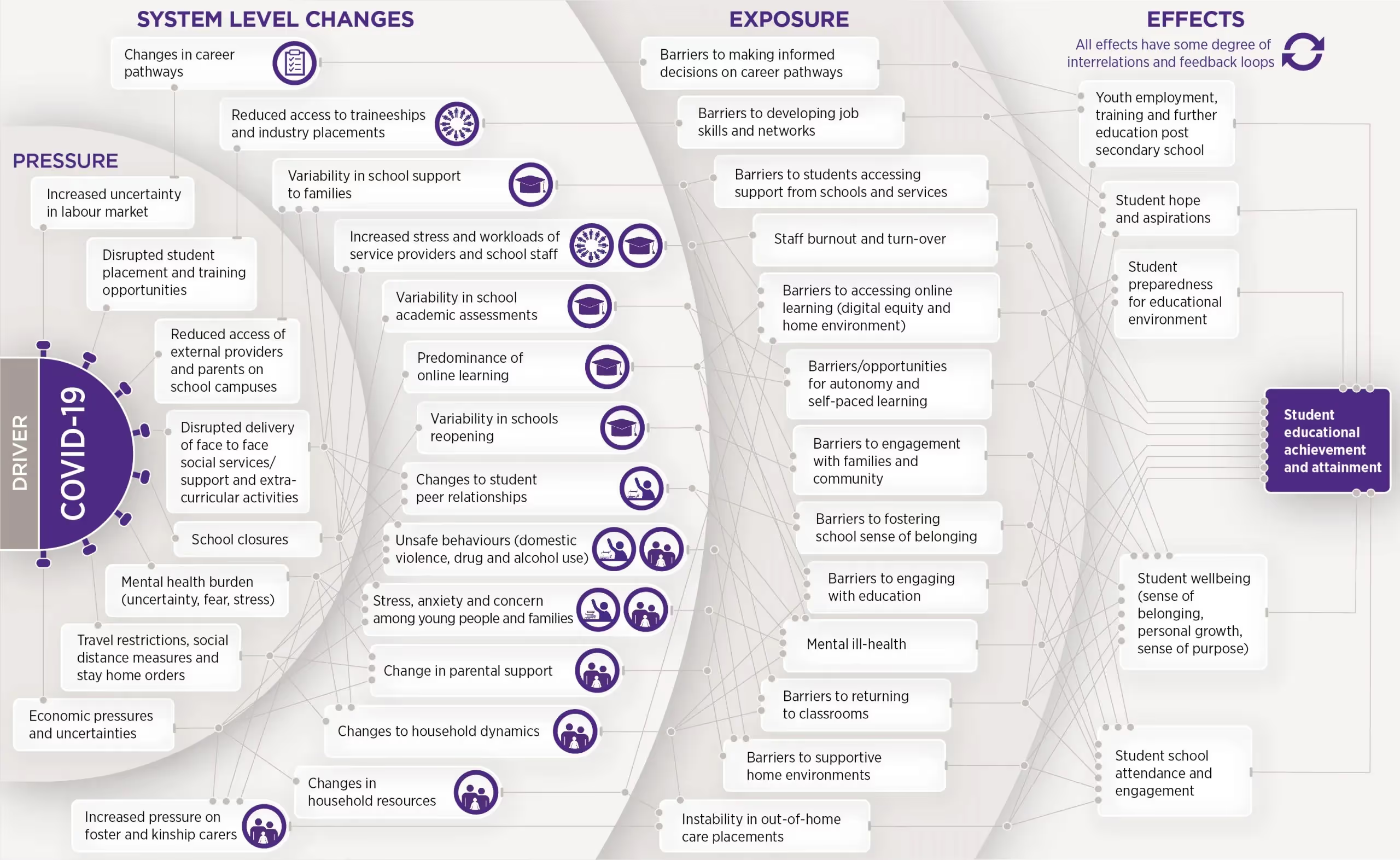

Drawing on the insights presented in the Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 reports, the Pillar 3 report presents an evidence-based driver tree that shows how the pandemic influenced factors within and outside school that in turn influence students’ educational outcomes. It also serves as a map that allows effort to be targeted where it can mitigate the effects of the pandemic on educational disadvantage.

Acknowledging that effective action may take place across drivers, the Pillar 3 report presents four priority action areas and, for each action area, 3-5 core actions based on evidence of what works and expert advice.

The Pillar 3 report also conducted a ‘what works’ review which identified 65 programs from Australia and around the world which have rigorous evidence for being effective in improving educational outcomes for the three disadvantaged cohorts in the study. These programs were rated not only for their effectiveness but also their readiness for implementation at some degree of scale. There are several key findings from this review:

- For most priority action areas, there is a clear trade-off between the proven effectiveness of programs and how ready they are to be implemented in Australia. Many programs that are currently running in Australia do not have rigorous evidence that they work, and most of the identified programs that are effective are overseas.

- There is no rigorous evidence of what’s effective in improving digital equity.

- Of the remaining three priority action areas, only a few programs have rigorous evidence that they are effective in protecting the most vulnerable students.

- Although there is robust evidence that high-dose tutoring can be effective in improving student achievement, the evidence base on how best to deliver tutoring programs is far from established.

- The report states that there is not clear evidence about “the optimal frequency, duration and mode of delivery for tutoring programs, particularly for children and young people from diverse backgrounds (for example Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people).”

- “There is also no evidence for how to deliver tutoring programs in rural and remote areas of Australia.”

Findings about Student Achievement

The Learning through COVID-19 study does not include any data on student achievement. We note that at least two other studies released late in 2020 address this issue. As reported in the Sydney Morning Herald in December, preliminary analysis provided by the New South Wales government suggests that on average, students did not make as much progress in their learning in 2020 as in previous years. The report also notes that teachers and principals raised concerns that those most disadvantaged before the pandemic have been most affected. Other work from Laureate Professor Jenny Gore and her colleagues at the University of Newcastle’s Teachers and Teaching Research Centre indicated that Year 3 students in lower-SES schools made less progress in maths than similar students in the year before the pandemic, but that they made similar progress in reading and science.

Implications

As described above, the premise of the Learning through COVID-19 study was to provide a more objective view of what happened for students experiencing educational disadvantage through the pandemic’s disruptions and to offer evidence-based options for action on the basis of those findings. Below we consider some of the key findings from the report and their implications for further action.

- 1. Knowing why educational disadvantage didn’t get worse during lockdown in NSW and TAS could provide insights into addressing pre-existing educational disadvantage in Australia.

The Pillar 2 report presents surprising findings that challenge the study’s original hypothesis. The report found that the gap on many educational outcomes did not widen between the cohorts of interest and more advantaged students. This high-level finding raises a key question: On balance, if students experiencing disadvantage were not further disadvantaged, what conferred protection during the COVID-19 shock? This question deserves further investigation, and answers could provide useful insights into addressing pre-existing educational disadvantage.

A wide range of factors should be considered, and the driver tree presented in the Pillar 3 report may provide a useful map of other causal chains for investigation. For example, it may be that the government’s JobKeeper scheme and changes to the level of payment under JobSeeker meant that there was less economic pressure and uncertainty on some families than there might have been, which flowed through to increases or little change in household resources and home learning environments that were manageable. Also, we are aware of efforts among philanthropy to address digital equity, some of which may have resulted in fewer barriers to accessing online learning than predicted.

Further, the experiences of young people experiencing disadvantage reported in Pillar 2 may provide some useful starting points, especially where the alternative provision of education seemed to confer some benefit, such as to students with sensory needs and mental health challenges. A key theme worth investigating, and highlighted in two of the core actions recommended in the Pillar 3 report, is flexible learning models, which the research team defines as “programs inside and outside schools that are designed to address the diverse needs of students, by tailoring what is taught and ways of teaching and learning to respond to those needs, whether these be related to mental health or educational outcomes.” For students with certain identifiable risk factors, do certain aspects of flexibility in their learning, including where they learn and support for their self-direction in learning, confer benefits to their continued engagement in learning and their achievement?

It would also be worth considering whether there may be other explanations for the findings here, and whether the findings hold true in Victoria, especially given its longer lockdown and remote learning period.

2. Existing governments initiatives can be built on to address the drop in attendance of senior students at risk of disengaging from school

Senior students at risk of disengagement saw their school attendance drop during the lockdown period, and comparing them against similar students in the previous year indicates that this drop was likely because of the pandemic disruptions. This cohort could be a target of specific attention to monitor whether their attendance patterns have gone back to normal and, if not, to seek to re-engage them with schooling. The evidence suggests that integrating high-dose tutoring with non-academic mentoring based in a cognitive-behavioural approach may be effective in addressing the needs of this cohort.

The NSW and Victorian governments are supporting high-dose tutoring programs in their states in response to COVID-19. As they are rolled out this year, where these programs target senior students at risk of disengaging, they could look to incorporate non-academic mentoring based in a cognitive-behavioural approach. Also, given that the evidence base for how to do high-dose tutoring in Australia is not robust, the roll-out of tutoring should include a monitoring and evaluation component to see what’s happening on the ground and what combinations of “frequency, duration and mode of delivery” are most effective. Particular attention should be paid to students from vulnerable cohorts, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students and those living in rural and remote contexts.

3. The relative lack of robust evidence for Australian programs demands that funders invest in rigorous evaluation to leave a legacy of knowledge

That works review reported in Pillar 3 shows that, for most Australian programs that are relevant to the priority areas for action, there is limited evidence of effectiveness. In the cases of digital equity and protections for the most vulnerable students, there are very few programs with demonstrated effectiveness, or even none at all. This lack of evidence leaves philanthropic and government funders in the challenging position of having to make decisions about how to address some pressing needs without an appropriate degree of confidence that better outcomes can be achieved. We would not accept that reality in other domains, as the global mobilization to produce and test COVID-19 vaccines demonstrates so well.

As funders start to support initiatives that will address the needs identified in these reports, they should also fund rigorous, independent evaluations of those initiatives, with a commitment to publicly report findings. This is especially true for initiatives to support digital equity, where there is no evidence. Funding evaluations in this way will both help us learn what’s working now and leave a legacy of knowledge, so that decision makers in the future will start from a better foundation.

The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered the largest disruption to education in modern history. The Learning through COVID-19 study has helped provide a more objective view of the impact on students experiencing educational disadvantage and offer evidence-based options for action. We hope this work will contribute to decisions focused on addressing the pandemic’s impact, as well as the broader discussion about effective interventions for ending educational disadvantage.

.png)